Por Sara Cody, Senior Editor at LACMA publications

In video recorded for public television in the early 1980s, Carlos Almaraz stands in front of a vibrant 12-foot depiction of a Los Angeles burrito stand and explains, «I see painting as a kind of time capsule. You put information on it, and you thrust it into the future, and you hope that someone will come into a gallery or a space, and ask what in the world this was.» The painting, Almaraz notes, may be the only evidence that the burrito stand—or any other particular place or moment in time—ever existed.

This interview is threaded throughout Carlos Almaraz: Playing with Fire, the documentary that premiered on Netflix on October 1, just in time for what would have been the artist’s 79th birthday on October 5. Directed by Elsa Flores Almaraz and Richard Montoya (and including interviews with LACMA’s director Michael Govan and contemporary curator emeritus Howard N. Fox, among many others), Playing with Fire dynamically illustrates how Almaraz’s work captured Los Angeles in the 1970s and 1980s with such insight and verve that his paintings occupy a space that is simultaneously highly specific and profoundly universal.

Taking its title from the retrospective held at LACMA in 2017, Playing with Fire chronicles Almaraz’s eventful life and spirited practice, beginning with his birth in Mexico City in 1941, his formative years in Los Angeles (by way of Chicago), and his move to New York in 1962 to pursue art. Eventually finding himself out of step with both the Pop and the Minimalist movements that dominated the New York scene at the time, he took a freighter to North Africa and traveled around Europe before finally returning to Los Angeles in 1970.

Though his homecoming seemed inauspicious at the time, it would soon prove pivotal. By 1971 Almaraz had become a political activist within the Chicano movement, and by 1973 he was producing illustrations and banners for the United Farm Workers. During this period Almaraz also cofounded Los Four, the influential artists collective that would make history in 1974 with their exhibition at LACMA—making Almaraz, Beto de la Rocha, Gilbert Lujan, and Frank Romero the first Chicano artists to show at a major U.S. museum.

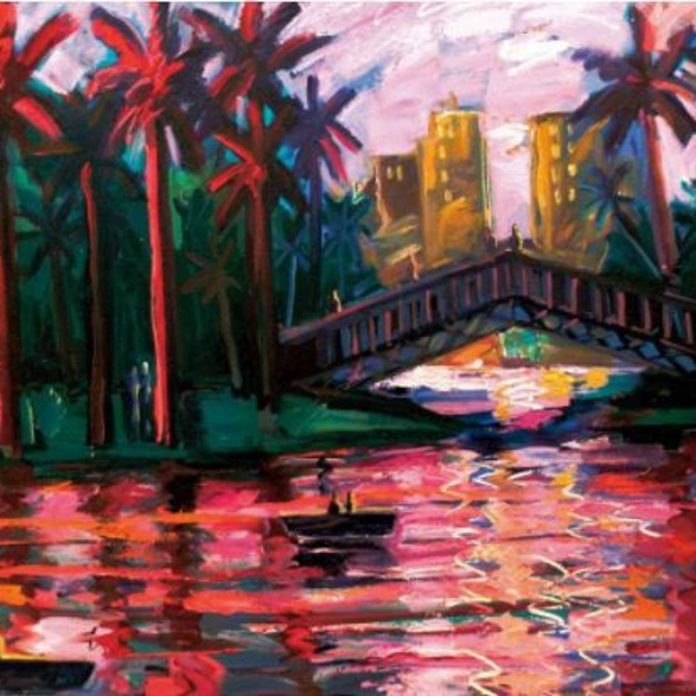

By the late 1970s, however, Almaraz was frustrated with the limitations he experienced in making primarily social and political art. Shifting his identity from that of a cultural worker to that of a studio artist allowed himself the freedom to create a breathtaking array of deeply personal paintings, prints, and drawings—works that are at turns ecstatic, lyrical, contemplative, witty, and dark. Among Almaraz’s most well-known works from this period are his vivid, almost cartoon-like car crashes and his serene, impressionistic views of Echo Park. While these themes are quintessentially L.A., the intensity and confidence of Almaraz’s vision means that they tap into fundamentally human experiences and emotions. More than 30 years after his untimely death in 1989, Almaraz’s work continues to speak to our lives as Angelenos, and to our dreams as human beings.